Ishmael Beah

Every time you save a child from war, there is hope. From child soldier to renowned author and human rights activist, the gripping story of Ishmael Beah, a U. Ishmael Beah is a keynote speaker and industry expert who speaks on a wide range of topics. The estimated speaking fee range to book Ishmael Beah for your event is $20,000 - $30,000. Ishmael Beah generally travels from New York, NY, USA and can be booked for (private) corporate events, personal appearances, keynote speeches, or other performances.

Ishmael Beah

January 04, 2015 Story 0003

Child Labor, Modern Slave Narratives, Forced Labor

Ishmael Beah was only 12 years old when a government army pulled him into the Sierra Leone armed conflict in 1993. Confused and afraid, Beah witnessed and participated in the atrocities of the civil war until he was rescued by UNICEF in 1996.

According to Beah, his life before the war was very simple but very happy. Life was peaceful, beautiful, and the people in his village were kind, trusting and amicable. They felt far from the rage and spread of the war’s turmoil. Beah was a growing boy, interested in American hip-hop, and lived a normal life with his family.

When he was just 12 years old, he and his friends left home to perform in a talent contest in a town a few miles away. While on the road, they found out that their village was attacked, so Beah and his friends ran back home only to face a horrific scene.

“We encountered people running,” he describes. “We saw men carrying their dead children in their arms. I saw a man cry for the first time in my life, so this really disturbed me quite a bit. So we decided that, you know, we can't go back home anymore and decided to wait. Hopefully to see our families come through, but they didn't come.”

With their homes destroyed and with their safety at risk, Beah and his friends roamed from village to village scrounging for food and water. After a year of wandering the countryside, Beah received news that his family was at a nearby village. As he approached the village, however, Beah only came upon gunfire, smoke and ashes. The whole village was burned down, and his family members were incinerated along with it.

Without a family to reconcile with, Beah lost hope and found no reason to keep running. Beah went to a village run by government soldiers. There was food, soccer games and places to sleep, and Beah though it was a good place to stay. Staying at the soldiers’ village came with a price.

“One day they just said, you know if you're in this village, you're gonna have to fight, otherwise you can leave... Some people tried to leave, but they were shot.”

He continues, “First, you know, you get your own weapon and everything and the magazines and the bullets, and then they give you drugs. I was descending into this hell so quickly, and I just started shooting, and that's what I did for over two years basically. Whoever the commander said, ‘This guy is the enemy,’ there were no questions asked. There was no second guessing because when you ask a question and you say ‘Why,’ they’ll shoot you right away.”

Using fear, indoctrination, cocaine, marijuana and brown-brown (cocaine mixed with gun powder), the government army turned Beah and other children into killing machines.

Beah explains, “What happens in the context of war is that, in order for you to make a child into a killer, you destroy everything that they know, which is what happened to me and my town. My family was killed, all of my family, so I had nothing. We had come to believe whatever our commanders were saying about how these other guys didn't deserve to live, that we were doing the right thing and this group was the only thing that was slightly organized; and so, they become like a surrogate family in a weird way.”

Beah says his lieutenant became his father figure, and it was that bond that helped United Nations (UN) workers rescue Beah from the armed group.

“The lieutenant went around and selected a few of us and said, ‘This man will take you and give you another life.’ And they took our weapons from us, and we actually felt that we were being pulled from family again.”

The UN workers brought Beah and other child soldiers to a rehabilitation center in Freetown. A year later, Beah spoke at the UN presentation of the Machel Report on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Children.

Today, Beah advocates for war affected youth. He's a member of the Human Rights Watch Children’s Rights Division Advisory Committee and a UNICEF Advocate for Children Affected by War. He co-founded the Network of Young People Affected by War and started the Ishmael Beah Foundation which assists in the reintegration of war affected youth.

Sources:

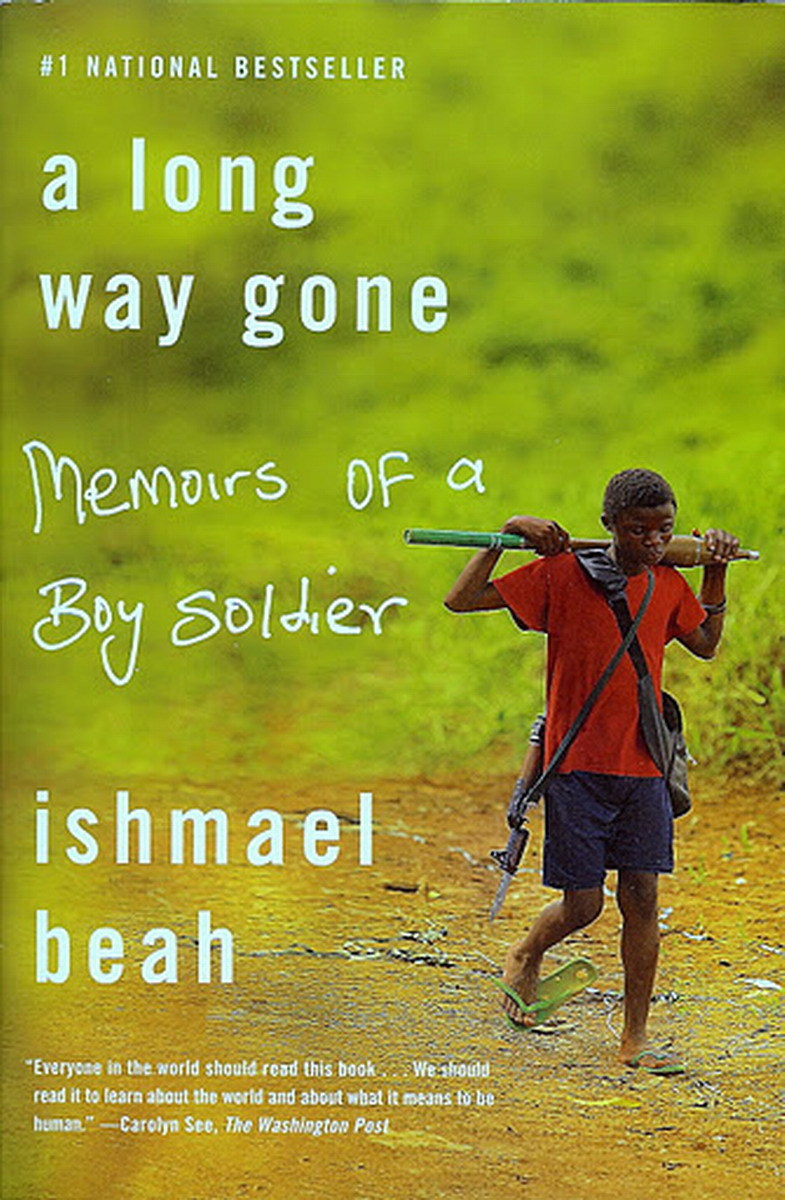

Beah, Ishmael. A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2007. Print.

Brown, Jeffrey. “Former Child Soldier Recalls Experiences in Sierra Leone.” Pbs.org. PBS Station, 05 Apr. 2007. Web. 27 May 2014.

“Ishmael Beah: Advocate for Children Affected by War.” UNICEF.org. United Nations Children’s Fund, 25 May 2012. Web. 27 May 2014.

Johnson, Caitlin. “A Former Child Soldier Tells His Story.” Cbsnews.com. CBS News, 03 Jun. 2007. Web. 27 May 2014.

- Ishmael Beah

- Best-selling author and human rights spokesperson, Advocate for Children Affected by War at UNICEF

- Links:

Beah offers hope out of great suffering

Ishmael Beah Books

What does war do to the human spirit?

This is the question that Ishmael Beah, widely known author of the New York Times bestseller, A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, tried to answer for the large January Series audience that came to hear him speak Friday.

In his quiet and measured tone, he explained why he was compelled to write his memoir during his last year at Oberlin College, a time when he could have been having fun and trying to forget what happened to him as a boy in his native Sierra Leone when a civil war erupted and he was forced to join in the violence. Beah knew he needed to do something with what had happened to him—he couldn't allow it to sit inside of him and make him perpetually angry. So with the help of a creative writing teacher, he set out to tell the story of his boyhood. He did so not only to tell his own story, but also to tell the story of so many others who were not as lucky as he was to escape from Sierra Leone and be adopted by a family in New York. He did so also to tell the world about Sierra Leone, and to show the humanity of these people who got sidetracked by anger and thirst for vengeance.

Beah said that he speaks in order to allow his story to go out from himself to be possessed by his listeners, reminding them about the humanity present in all and the equal capacity among all human beings to act violently out of anger and hatred towards each others. He also wants his listeners to see the hope that exists even in the most dark and violent places when people do things to help each other. He found this when villagers would give him food, even though he was part of the violent forces in Sierra Leone. He found this when a UNICEF worker rescued him from the violence in his country, and again when a family in New York adopted him and gave him an opportunity for a new life in the United States.

Speaking about writing his memoirs, Beah said that his writing style appeals to many readers because of the creativity he must use when translating images from his native context and language into English. He also said that his writing is enriched by the oral traditions of storytelling he received in his village before the civil war began. Active listening, he said, is something that we must all learn to do better in order to tell good, truthful stories. This tool was helpful for him when writing his memoir years after the events depicted actually occurred; he was able to remember and faithfully record the events of his life.

At the end of his talk, Beah spoke about the importance of education in his rehabilitation process after leaving Sierra Leone. Education showed him that there is more to life than violence and suffering. It also showed him his place in the world—one in which he can help others and forever be grateful that he was given a second chance at life.

More about the speaker

Ishmael Beah was born in Sierra Leone on November 23, 1980. When he was eleven, Ishmael’s life, along with the lives of millions of other Sierra Leoneans, was derailed by the outbreak of a brutal civil war. After his parents and two brothers were killed, Ishmael was recruited to fight as a child soldier. He was thirteen. He fought for over two years before he was removed from the army by UNICEF and placed in a rehabilitation home in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. After completing rehabilitation in late 1996, Ishmael won a competition to attend a conference at the United Nations to talk about the devastating effects of war on children in his country. It was there that he met his new mother, Laura Simms, a professional storyteller who lives in New York. Ishmael returned to Sierra Leone and continued speaking about his experiences to help bring international attention to the issue of child soldiering and war affected children.

In 1998 Ishmael came to live with his American family in New York City. He completed high school at the United Nations International School, and subsequently went on to Oberlin College in Ohio. Throughout his high school and undergraduate education, Ishmael continued his advocacy work to bring attention to the plight of child soldiers and children affected by war around the world, speaking on numerous occasions on behalf of Unicef, Human Rights Watch, United Nations Secretary General’s Office for Children and Armed Conflict, at the United Nations General Assembly, serving on a UN panel with Secretary General Kofi Annan and discussing the issue with dignitaries such as Nelson Mandela and Bill Clinton. He is a member of the Human Rights Watch Children’s Rights Division Committee.

In A Long Way Gone, Beah, now twenty-six years old, tells a riveting story. At the age of twelve, he fled attacking rebels and wandered a land rendered unrecognizable by violence. By thirteen, he’d been picked up by the government army, and Beah, at heart a gentle boy, found that he was capable of truly terrible acts. Eventually released by the army and sent to a UNICEF rehabilitation center, he struggled to regain his humanity and to reenter the world of civilians, who viewed him with fear and suspicion. This is, at last, a story of redemption and hope.

Presentations at Calvin University

A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy SoldierPart of the: January Series

Friday, January 11, 2008 12:30:00 PM (12:30 PM–1:30 PM EST)

Covenant Fine Arts Center Auditorium

Underwritten by: John & Mary Loeks

Due to contractual restrictions, this presentation was not recorded or archived.

Featured publication(s)

Ishmael Beah Family

- Course code:

- Credits:

- Semester:

- Department: